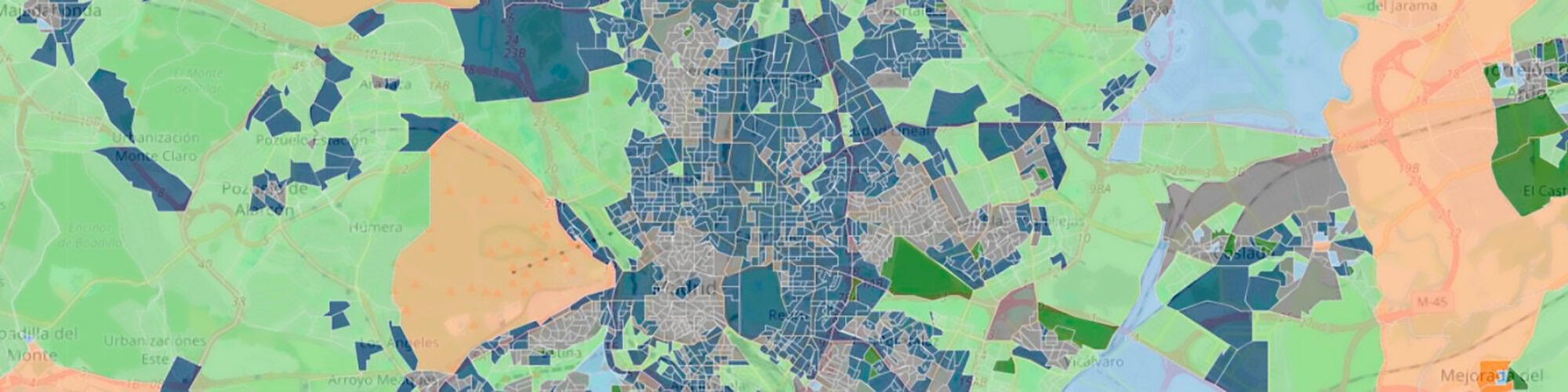

A few years ago he wrote an article entitled Cities and portsa study in which he explained the processes of transformation of disused port areas in various cities. Rather than focusing on the architectural details, Alejandro Grindlay Moreno (Málaga, 1970) focused on the processes and what happened in Spain in recent decades. A lecturer at the University of Granada, where he teaches in the area of Urban and Regional Planning in Caminos, Grindlay shows that the problems currently being experienced in A Coruña with regard to the remodelling of the coastal façade are by no means a unique issue. What is happening in A Coruña has happened in many other places.

-Are the relations between port authorities and municipalities always so complicated?

-In Spain, until the 1990s, there was a period of very defensive postures on the part of the port authorities, always with a view to making their land profitable. This vision began to change in 1992 (Barcelona) but was maintained until the beginning of the 21st century.

-How have these relationships changed?

-The doors are now more open to urban demands. Social pressure has also helped. With the 1997 legislation, ports became more open with boards of directors involving more social participation in their governance.

-What has generated tensions?

-The port authorities have the legitimate objective of maximising their turnover, and many have seen the business in the transformation of the ports themselves. In the case of A Coruña, moreover, the outer harbour is a burden on the accounts. But this is not new. In Malaga, what is now a marvellous park, were going to be plots of land at the end of the 19th century, and were not thanks to the intervention of Cánovas del Castillo.

-How can solutions be reached?

In all these operations, politicians should be thinking about the long-term good of the city. The problem is when the horizons are short term. These actions have to be thought of in 10 or 20 years' time. Many people here are not capable of transcending short-termism and electoral gain, they do not see the success in seeking agreement. It seems that if you don't put obstacles in the way of the government you are not doing your job properly. In Granada, for example, this happened with the light rail, and something that was going to be done in three years ended up taking ten.

-What should be done in A Coruña with what will be freed up?

-Once it is disaffected, whatever is decided. But I think that what enriches these operations is the mix of uses, so that they don't end up becoming a gentrified neighbourhood. It would be desirable to have a mix of facilities, social housing and free housing. This is what Busquets proposed and in this sense the plan was very careful, although what is proposed is one thing and what is done is another. The risk is that the final result will not be what was originally envisaged.

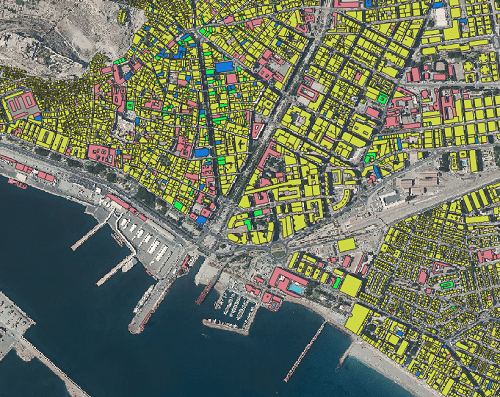

-What are the most frequent models of port transformations?

-The American model is more focused on leisure and consumption, in a certain way. disneylanisation. This building intensity was also seen in London. In the rest of Europe they tend to be more careful, with more respect for heritage. I believe that if something has been a port, it cannot be replaced by a shopping centre, something must be maintained. In Barcelona, for example, the Maremagnum responds to the American model, and in Alicante there has also been a very important tertiary component. In Malaga, the first plans were for a large shopping centre, but in the end something more open-plan, more distributed, was achieved. Being able to recover the port buildings is something that gives a lot of play, it was done in Tarragona and also in Valencia.

-There will be differences according to the surface to be tackled.

-It's all a question of scale. The more surface area, the more play, and A Coruña has it. Bilbao is the paradigm of this model and the key there was the agreement between administrations of different political colours rowing in the same direction. In Bilbao there was a very powerful technical office, as in Vitoria with the Green Belt, and that is important, as is having a roadmap despite political and economic vicissitudes.

-In A Coruña there was an agreement in 2004. What has changed since then?

-In 2004 we were rich and we were booming, there was funding to do whatever we wanted. Now that is unfeasible. Of course, if there was a consensus in 2004, that plan can always be updated, but I think the basic premises that led to the agreement should be maintained.

The 2004 agreement was more than an urban development agreement, it was a plan to obtain resources to finance part of the Langosteira project. The outer harbour would not have been built if an agreement for its financing had not been reached in 2004. For years now, the current situation and the realism of this pact, sealed on four sides between the City Council, the Xunta, the Port Authority and the Ministry of Public Works, have been on the table.

At the time, urban developments offered substantial and immediate resources. The pre-crisis situation made it possible, for example, to carry out a large part of the renovation of Bilbao, slowing down the pending developments in that city, which also radically changed the façade of the estuary and where the sale of land for housing construction has a strong presence.

In A Coruña, the 2004 model foresaw, among other things, a new shopping centre in the most central docks, an idea that, after the closure of Dolce Vita and the change of use of Los Cantones Village, lost weight in the city. The plans for Batería and Calvo Sotelo have been put on hold after the arrival of the Xunta, which has already said it will redefine the uses. The fact that the general plan includes 54,000 square metres of developable land there does not mean that the owner is obliged to implement them. And the Xunta, which will take over the land, has already said that its intention is not to redefine the future uses of the land. This statement implies a negotiation with María Pita, because without the City Council, the general plan cannot be modified.

It remains to be seen how action will be taken in San Diego. There were 4,000 dwellings planned and that is in the plan. The future of this area remains to be addressed.

Part of the information in this news item has been obtained from the web site of La Voz de Galicia

Correo electrónico: info@gis4tech.com